John Coffee’s One Weird Trick to Push Lifters to Their Full Potential

by Edward Baker

It’s finally time for people to know: How did the relentless John Coffee push his lifters to their full potential?

He didn’t. He held them back instead.

As I was growing up and playing sports, I came to believe that based on how I was coached, that being a coach entailed motivating and psyching up athletes. It meant helping athletes learn how to reach their full potential by pushing them harder than they’ve ever been pushed. In the football strength & conditioning community, you hear of head coaches talk of how great their strength coach is by their ability to ‘motivate and push the players inside and outside the weight room’. Once I started working with John, his attitude towards my training said otherwise. I wouldn’t consider myself the hardest worker in the world, but I have trained to injury to the extent that I would have trouble walking and sitting, and John would have to step in to stop me from worsening my injury to the point that it became completely debilitating. A phrase that he said to me years ago has stuck with me:

“From my experience, being a coach is more about holding someone back then pushing them harder. Everyone wants to go heavier”.

Mental toughness is an ability that’s cultivated through years and years of successes and failures; that can be in a sport, in school, or just life in general. Many of the athletes that I’m fortunate enough to work with have a background in gymnastics, and make me look like a baby. They’ve ripped off a torn callus mid set and kept lifting where I would have stopped to tape my hands up and start over. There have been more serious issues that they would gladly push through on their own will.

John has had lifters in meets hyperextend their UCL after a missed Snatch and they would insist to go out and make another attempt, yet he would step in and pull them out of the meet. This very instance happened to me at the 2011 Junior Nationals. I had one more attempt and wanted more than anything to make the lift. He withdrew me from the meet, and told me “I know you’re pissed off, I’m a little pissed off too. But you don’t want to (mess) with an elbow injury. This is something that could take a week or two to recover, but chances are if you go out for another attempt while the ligament is lax, then you’ll go and blow it out”. Sure enough, two weeks later and I was back to putting weights overhead again. I’ve seen others whose coach made the other choice, and they in fact blew their UCL out.

In training, he is very much the same way. He has a rough plan of what he wants his lifters to do each day, but nothing is set in stone and is based appropriately on how the athlete says that they’re feeling and how the warmup sets look. When the athlete gets to what John deems as a top working weight, he’ll say “that might be a good weight for today”. Most of the athletes that he has worked with are plenty self-motivated, and always want to put more weight on the bar. Sometimes with convincing John will allow the lifter to go heavier, but there are also times that he will put his foot down and keep them there as well. One of the only times I’ve ever been cussed out by John was when I decided to go heavy on the Clean & Jerk on a day that was supposed to be moderate. I still remember Kelly and Caleb Williams asking if I was okay after he left the room.

Pushing an athlete to fight through their physical limits in the incipient stages of their lifting career (when they may not have yet acquired the resilience that takes time to develop) is tantamount to expecting an athlete to perform too much weight for too many reps; their body is simply not capable of it. If an athlete like CJ Cummings fell into the hands of a coach that wanted to push him hard right from the get go, I wonder If he would have stuck around to win the International meets and break the World Records that he has. It also makes me wonder how many potential lifters there are out there that will be turned off by a coach who expects the world of them on day one? It’s incredibly tempting for coaches to stumble across a talented athlete and become greedy and push them to improve at the expense of their enjoyment of the sport or worse, at the expense of their physical well-being. John is never one to boast about the personal accomplishments of his lifters, but he is always proud to say that in his coaching career a Weightlifter under his guidance has never required surgery.

In my article Misconception of Developing Strong legs that appeared in the December 2014 issue of the USA Weightlifting e-magazine, I wrote something that I still feel is relevant today:

“One can take a look at the training system of the weightlifting superpowers of the world and mistakenly presume that mimicking their training program will yield excellent performances, when they have little relevance to athletes that don’t have the training backlog of their much stronger counterparts, don’t have the leisure of training as an occupation, and must attend an educational institution or work a full-time job.”

I’d like to say that I take my training seriously, but if the livelihood of me (and a possible family) were at stake based on my performance in this sport then I could certainly see how my mentality would change. That isn’t the case in this country though, and it’s only recently that some Weightlifting coaches in this country can make a living just coaching. I’ve heard the argument that coaches don’t want to push their athletes hard enough because they want them to stick around and keep paying; John coached during a time where there was no money to be made at all (he actually gave up plenty) and did so in the ‘hold them back’ fashion, so that decimates the argument that he does so to get his lifters to ‘continue to pay him’. It also makes me wonder if a Weightlifting coach’s salary in other countries is dependent on their athlete’s performance in competitions as well? If mine were, I could see how I might push lifters harder than ideal. It’s easier to push someone else rather than oneself to the brink of injury; if it’s someone else and they do in fact get hurt, that someone else is the one stuck with living with that injury.

I’m only slightly familiar of the physiological effects of anabolic steroids based on what I’ve learned in my college education along with second hand knowledge, but it seems to be that steroids (and other performance enhancing drugs) enable one to train harder and more frequently. Could this be juxtaposed with the use of the stimulant Adderall on children with ADHD:

Say that holding (presumably) drug-free athletes to the same standard as steroided athletes in their ability to train hard and frequently would very loosely be analogous to expecting children with ADHD that aren’t administered Adderall to perform to the same level in the classroom as children with ADHD that are (in terms of the reduction of inattentive and oppositional symptoms). This is not to completely discredit the Weightlifting superpowers of the world by throwing out the word steroids, but it should be noted that it does cause a significant change. That’s why they’re used in the first place.

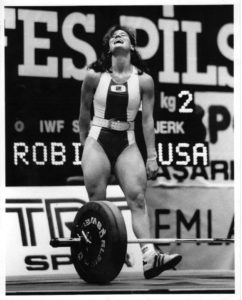

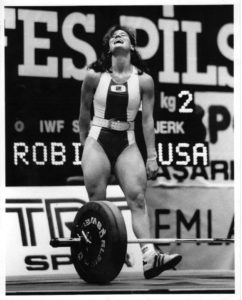

Perhaps the times are changing and John’s approach to coaching is becoming more irrelevant as Weightlifting moves more towards a sport where lifters can make a little bit of a living competing. It could very well be that his success was just happenstance, and that he was in the right place at the right time. Or perhaps his lifters could have performed even better with the quality of lifting overall in this country being higher? Maybe Robin Goad could have done more than an 80 kg Snatch and 100 kg Clean & Jerk as a 48 kg lifter (when she was 30) had she not been lifting to break her own National Records and to beat the World Standard in her weight class in her earlier years? I honestly find it quite fascinating that many different approaches are used in this country, and that many are successful. Success will speak for itself, or as Bob Hoffman would say, “Proof is in the puddin’”!

Also, A few weeks ago I posted this Facebook status:

Question to experienced coaches: In your experience, do you find that you more commonly have to push talented athletes to try heavy weights, or hold them back from doing so?

Here are a couple of responses from authorities:

“Easily, hold them back. No question. The best athletes are HUNGRY for heavier weights but also usually have some sense of when the right time may be. If the coach has their trust, and can be completely objective on their behalf, it can be a powerful partnership.” – John Thrush

“Talented lifters or not, coaches are often challenged to hold a lifter back. Many times that’s what’s needed for long-term progress. Developing lifters are more likely to be the ones that need encouragement to attempt lifts they may think are beyond their capabilities. Here we encounter the science of coaching vs. the art of coaching.” – Harvey Newton